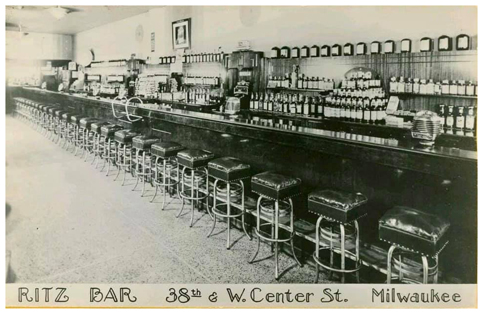

The Ritz Bar brings back fond memories of cheeseburgers and fish fries to those who lived in Milwaukee, Wisconsin during the ’50s and ’60s. The history of the establishment goes even further back with its flashing identity sign that possibly dates all the way to the ’40s.

The face of the Ritz Bar sign was made out of porcelain. It featured stainless letters with incandescent chaser bulbs in the middle and neon tubing surrounding the letters.

And while the Ritz Bar is no longer a part of the modern Milwaukee landscape, the good news is that its long-standing sign was recently rescued. Read on to find out how this vintage sign was restored to its former glory for the first time in nearly sixty years—bullet holes and all.

History in the Making

Joe Anderer is a sign collector who lives in the Milwaukee area, and he was thrilled to have come across the Ritz Bar sign last year. However the at-the-time non-functional sign had seen better days.

Anderer was a regular customer of Bauer Sign & Lighting in New Berlin, Wisconsin, so he gauged their interest in restoring this sign. “We had done a few other neon-on-porcelain restorations for [Anderer] over the past couple of years, so we were happy he brought this project to us,” says Chris Stemper, a tube bender and lighting specialist at Bauer Sign & Lighting who took the lead on this project.

Bauer Sign & Lighting is a full-service sign company with around twenty-five employees that has been around since 1982 (all under the same owner, Jim Bauer). The company manufactures, services, and installs mostly electrical signage in the Wisconsin and northern Illinois area.

Stemper also happens to be in the same “Old Milwaukee” Facebook group where Anderer is a member. Anderer’s post about his sign discovery in that group had already caught Stempe’s attention. “He had saved it from getting scrapped,” says Stemper.

The Ritz Bar sign arrived at Bauer Sign & Lighting as two separate, carefully crated porcelain panels. “The stainless steel letters were all intact and in very good condition other than being dirty and stained by years of rain, snow, and smog,” says Stemper.

But everything else needed tender-loving-care attention in order to bring it back to life. “The porcelain faces needed a new cabinet, all-new sockets, bulbs, brass hardware, a mechanical flasher, and of course, neon,” says Stemper.

Stemper had to put on his detective hat for a couple of instances. One was figuring out the color of neon to use on the sign.

All the neon was missing—except for one broken center unit in the letter “A.” However this proved an important piece. “This sole letter was enough to determine with an ultraviolet light that the tube phosphor was standard blue,” says Stemper. “The fact that there was no evidence of mercury in the unit or electrode told me that it was likely filled with neon. This is how we determined the neon color was pink.”

All the neon housings were also missing, so Stemper had to study the hole sizes on the porcelain. “I concluded that the housings were #200s,” he says. “The back of the panel left me some questions that would be answered once work began.”

Nearly all of the 221 sockets were still in place. However, although all the 11w incandescent bulbs were still in the sockets, not a single one still worked after all the years of inactivity. The cloth jacketed primary wires were all there, as well. “This wire would obviously have to be replaced, as it was exposed in numerous places where the jacket had deteriorated,” says Stemper. “The backs of the sockets had all been covered with tar, which I assumed was done to provide some protection against any water intrusion.”

Stemper wasn’t sure he was going to be able to save the sockets, but he intended to do as much as he could to keep them.

He removed the sockets and soaked a few of them in lacquer thinner overnight to dissolve the tar. The next morning, he fished them out. “I discovered all the wires had been soldered to the their respective screws on the sockets,” says Stemper. “In addition, the tar soup that resulted from soaking them had seeped into the socket cup, making it a sticky mess.”

The decision was made: His team would opt for new sockets instead. This would provide a quicker solution and avoid spending unnecessary time trying to resurrect them. Stemper ended up using Leviton 9885 sockets and installing new 11w incandescent bulbs.

Stemper combined the neon primaries. “The incandescents had originally been split into six lines and one neutral,” he says. “This told me it was likely a scintillating effect. The connections to the sockets were mapped, as I removed the six lines one by one. The new wire was run in the same pattern.”

An FMS model 66 timer provides the scintillating effect today. “The secondary load of the neon was split into three Allanson SS935OX 120V/35 mA electronic transformers,” says Stemper. “We chose electronics over magnetic models to save weight on the sign, as each porcelain panel was already 150 to 200 pounds.”

In Depth About the Cabinet

There was some debate beforehand on how deep the cabinet should be to keep the structure stiff without adding any excess weight. Since the two porcelain panel faces were stacked, head fabricator Tony Camacho built a 72-by-72-inch, 6-inch-deep cabinet out of non-galvanized sheet metal.

Stemper explains that the faces had a one-half 90-degree bend, which made fabrication fairly simple. “The return only need a one-inch bend on the back,” he says. “It was screwed flush to the porcelain face with #8 brass screws and nuts.”

The only structure necessary was a cross of two-inch angle centered from top-to-bottom and side-to-side flush to the back. “The back panel was divided into four sections, which allowed full access to the interior,” says Stemper. “We added a mounting bracket for the model 66 timer to one side of the cabinet.”

Bauer Sign & Lighting used brass-based tube supports on the neon and brass fasteners to secure the sockets, letters, and the face to the cabinet. “We saved as much of the old fasteners as we could and used them again in the restoration,” says Stemper.

Stemper prefers to use brass hardware with porcelain. “Brass gives the porcelain an old-school look, and it also helps keep rust from developing and staining the surface,” he says.

Anderer was upfront that he didn’t want Stemper to make the sign too pretty. He still wanted it to look like it had some history to it. Stemper had to give the new cabinet a rusted-out appearance to match the rest of the sign, so he took a cue from the playbook of This Old House host Bob Vila and applied a “tried-and-true” method for “aging” metal.

After the sign was complete and the back placed on it, Stemper wiped down all the surfaces of the non-galvanized sheet metal with lacquer thinner to remove any oil from the surface. He then sanded it lightly with a 120-grit pad.

Next Stemper filled a spray bottle with white vinegar and sprayed all the exterior surfaces of the cabinet using a very light mist. “The acid in the vinegar immediately began to etch the surface,” he explains. “You can repeat this process as many times as you think you’ll need.”

After waiting about twenty minutes, Stemper then mixed a solution featuring 2 cups of hydrogen peroxide, 1/2 cup of vinegar, and 1-1/2 teaspoons of salt. He shook it up in another spray bottle and mist-sprayed all the surfaces with it. “You’ll see the peroxide bubbling up and building a nice patina of rust,” he says. “You can repeat this as necessary.”

Satisfied with the look, Stemper lightly sealed the surface with a clear coat. “Go too heavy, and you’ll get a shine,” he says. “A light coat keeps the rust from rubbing off and preserves the look.”

Taking Aim at Not Erasing History

As mentioned earlier, the porcelain panels featured real bullet holes.

“As is often the case with old signs, the neighborhoods in which they are located change over time,” explains Stemper. “In the ’50s and ’60s, this was a tight neighborhood with a nice little retail block full of other businesses besides the Ritz. Things changed though, and crime and gunplay became more common.

“The sign took a few hits—a .45 caliber exit hole on one side of the panel and two .22 caliber holes on the other side.”

As mentioned earlier, Anderer was more interested in making sure the restored sign still looked like it had some history behind it. “He told us to leave the bullet holes alone,” says Stemper, noting that these bullet holes actually give the flashing sign even more personality.

Restoration Reaction

The restored Ritz Bar sign now resides in Anderer’s garage, where he keeps a lot of the other classic signs in his collection.

Stemper enjoyed doing this restoration and finds that fixing and restoring a sign like this is fun for him on two different levels. “I’m always impressed by the craftsmanship from the heyday of these porcelain signs,” he says. “The stainless steel letters on this particular sign were flawless.”

“But on a more impressive note is how many memories are triggered in people who knew this sign and this business. We never could’ve imagined the positive response this sign got when it was posted on the Old Milwaukee Facebook page.”

Note: To listen to a podcast interview with Chris Stemper featuring more details about how this project was put together, as well as his thoughts on illuminated sign restorations, click here.

—Jeff Wooten